Gastrointestinal campylobacteriosis, caused by Campylobacterjejunior Ccoli , is associated with diarrhea in various animal hosts, including dogs, cats, calves, sheep, ferrets, mink, several species of laboratory animals, zoo animals, and humans. In humans, it is a leading cause of diarrhea. Cjejuniand Ccoliare also recovered from feces of asymptomatic carriers. (See alsobovine genital campylobacteriosis, Bovine Genital Campylobacteriosis: Introduction). Animals, including dogs and cats (especially those recently purchased from shelters), and wild animals maintained in captivity can serve as sources of human infection. The agents also are isolated frequently from the feces of chickens, turkeys, pigs, and other species. The organism commonly contaminates poultry meat, which serves as one of the major vehicles of spread of Cjejunito humans.

The disease is found worldwide; its prevalence appears to be increasing as proper culture techniques for C jejuni and C coli are refined and updated. Clinical manifestations may be more severe in younger animals. In studies using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies, Campylobacter spp (including C jejuni ) have been associated with proliferative ileitis in hamsters and proliferative colitis in ferrets. A cause and effect relationship has not been proved experimentally, however. Proliferative bowel disease in these animals is now known to be caused by Lawsonia intracellularis .

Etiology:

Campylobacter is a gram-negative, microaerophilic, slender, curved, motile bacterium with a polar flagellum. C jejuni is routinely associated with diarrheal disease; however, C coli , distinguished from C jejuni on the basis of hippurate hydrolysis, is occasionally isolated from diarrheic animals and is routinely recovered from asymptomatic pigs. Other intestinal, catalase-negative campylobacters, C upsaliensis and C helveticus , have been isolated from diarrheic dogs and cats as well as asymptomatic dogs and cats. Campylobacter was once associated with swine dysentery ( Swine Dysentery), but this is now recognized as being caused by Treponema hyodysenteriae . Most believe that Campylobacter spp do not produce porcine proliferative enteritis ( Porcine Proliferative Enteritis), even though a new organism, C hyoilei , isolated from swine in Australia, has been associated with porcine proliferative enteritis. Its role in this disease, however, is not clearly established. C mucosalis and C hyointestinalis have also been isolated from swine but are not considered enteric pathogens.

Because of slow growth and microaerobic requirements, standard culture methods require selective media that incorporate various antibiotics to suppress competing fecal microflora. C jejuni and C coli grow well at 42°C in an atmosphere of 5-10% carbon dioxide and an equal amount of oxygen. Cultures are incubated 48-72 hr; colonies are round, raised, translucent, and sometimes mucoid. The organism can be identified by a series of biochemical tests readily available in any diagnostic laboratory. Recently, PCR assays have been used to identify Campylobacter spp . Identification is important to distinguish campylobacters from the growing number of novel enterohepatic helicobacters being isolated from a variety of animals.

Transmission and Epidemiology:

As with most intestinal pathogens, fecal-oral spread and food- or waterborne transmission appear to be the principal avenues of infection. One suspected source of infection for pets, as well as mink and ferrets raised for commercial purposes, is ingestion of undercooked poultry and other raw meat products. Asymptomatic carriers can shed the organism in their feces for prolonged periods and contaminate food, water, milk, and fresh processed meats (including pork, beef, and poultry products). The organism can survive in vitro at 41°F (5°C) for 2 mo and can survive in feces, milk, water, and urine. Wild birds also may be important sources of water contamination. Unpasteurized milk has been cited as a principal source of infection in several human outbreaks. Strain identification to study the epizootiology of C jejuni and C coli , in addition to Penner serotyping, is now done using molecular techniques such as restriction fragment length polymorphism and ribotyping.

The diarrhea appears to be most severe in young animals. Typical signs in dogs include mucus-laden, watery, and/or bile-streaked diarrhea (with or without blood) that lasts 3-7 days; reduced appetite; and occasional vomiting. Fever and leukocytosis may also be present. In certain cases, intermittent diarrhea may persist >2 wk; in some, it may be present for months. Gnotobiotic puppies inoculated with C jejuni developed malaise, loose feces, and tenesmus within 3 days of inoculation.

In calves, signs vary from mild to moderate. The diarrhea is thick and mucoid with occasionally visible blood flecks; body temperature may be normal. Diarrhea with mucus and blood also has been observed in primates, ferrets, mink, and cats. Organisms with ultrastructure similar to that of Campylobacter spp have been seen in hyperplastic ileal epithelial mucosa of hamsters with proliferative ileitis; C jejuni has been isolated from these lesions but has failed to reproduce the syndrome. Organisms with Campylobacter -like morphology also have been associated with proliferative colitis in ferrets and with hyperplastic intestinal lesions in guinea pigs and rats. Campylobacter -like organisms have been described in young rabbits with acute typhlitis. It is now known that these organisms are Lawsonia intracellularis , an organism closely related to Desulfovibrio spp .

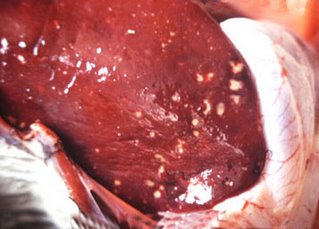

In 3-day-old chickens infected with C jejuni , the organisms were detected within epithelial cells and mononuclear cells of the lamina propria; the jejunum and ileum were the most severely affected. Congested and edematous colons were found in dogs 43 hr after inoculation; microscopically, epithelial height, brush border, and numbers of goblet cells in the colon and cecum were all reduced. Hyperplastic epithelial glands resulted in a thickened mucosa. Histologic changes in calves primarily involve the jejunum but also can involve the ileum and colon. The lesions vary from mild changes to severe hemorrhagic enteritis. The mesenteric lymph nodes are edematous. Experimentally, some strains of C jejuni produce a hepatitis in mice, and the organism has been isolated from inflamed livers of dogs. A cytotoxin, referred to as cytolethal distending toxin, has been identified in C jejuni ; however, its role in production of intestinal disease is not known. In vitro, the cytotoxin causes distention of cell lines and cell cycle arrest in the G2M1 phase of the cell cycle.

Diagnosis:

The standard method for diagnosis is microaerobic culture of feces at 42°C; a special medium is commercially available. Diagnosis is also possible by using darkfield or phase-contrast microscopy, by which fresh fecal samples are examined for the characteristic darting motility of C jejuni . This method is especially useful during the acute stage of diarrhea when large numbers of organisms are more likely to be shed in the feces. Various techniques can detect serum antibodies to various antigens of Campylobacter spp . Heat-stable or heat-labile antigen schemes are used routinely to serotype various strains. Serial serum samples to demonstrate rising antibody titers are helpful in diagnosis. Intestinal viruses and other intestinal bacterial pathogens must be ruled out as primary or copathogens in animals with Campylobacter -associated diarrhea.

Treatment and Control:

Isolation of C jejuni or C coli from diarrheic feces is not, in itself, an indication for antibiotic therapy. Because C jejuni and C coli are not routinely cited as potential intestinal pathogens in animals (except for diarrhea in young cats and dogs and in several species of primates), efficacy of antibiotic therapy has been reported infrequently. In certain cases in which animals are severely affected or are a zoonotic threat, antibiotic treatment may be indicated. In general, C jejuni and C coli isolates from animals are similar to isolates obtained from human populations. Erythromycin, the drug of choice for Campylobacter diarrhea in humans, is also effective in other animals, although erythromycin-resistant strains of Campylobacter spp have been recovered from swine. Gentamicin, furazolidone, and doxycycline also can be used. Ampicillin is relatively inactive against most strains of Campylobacter , and most strains are also resistant to penicillin. Tetracycline and kanamycin resistance in certain C jejuni strains is reported to be plasmid-mediated and transmissible within C jejuni serotypes. Efficacy of sulfadimethoxine and sulfa combinations is variable. Before therapy is instituted, isolation and sensitivity tests should be done. Some animals continue to shed the organism despite antibiotic therapy. Quinolone antibiotics may be useful in eliminating C jejuni and C coli in asymptomatic carriers, but drug resistance may develop.

taken from themerckvetmanual

No comments:

Post a Comment